Terence McKenna was an American ethnobotanist, philosopher, psychonaut, lecturer, and author who was born on November 16, 1946, and passed away on April 3, 2000. He was well-known for his extensive research and exploration of psychedelic substances, particularly ancestral plant medicines, such as psilocybin mushrooms, ayahuasca, ibogaine and 5-MeO-DMT.

Like us here at Ibogaine Treatment UK (Iboga Root Sanctuary), McKenna was a strong advocate for the therapeutic use of naturally occurring psychedelic substances as a means for exploring consciousness, personal growth, and healing from trauma.

Parallel to his work was his theory—controversial to this day—that of all known entheogens (naturally occurring psychoactive substances), psilocybin mushrooms were the likely “culprit” in the emergence of human consciousness.

According to him, their psychoactive effects were instrumental in shaping human culture, from our early ancestors like Australopithecus to more advanced forms like Homo Habilis, Homo Erectus, and ultimately Homo Sapiens.

According to McKenna, our early ancestors may have accidentally stumbled upon these psychedelic fungi.

In his seminal work published in 1992, “Food of the Gods; The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge: A Radical History of Plants, Drugs and Human Evolution,” he maintains that psilocybin alone may have caused the development of language, art, and religion—that is, human consciousness and the ability for abstract thought.

Climate Change 1.0

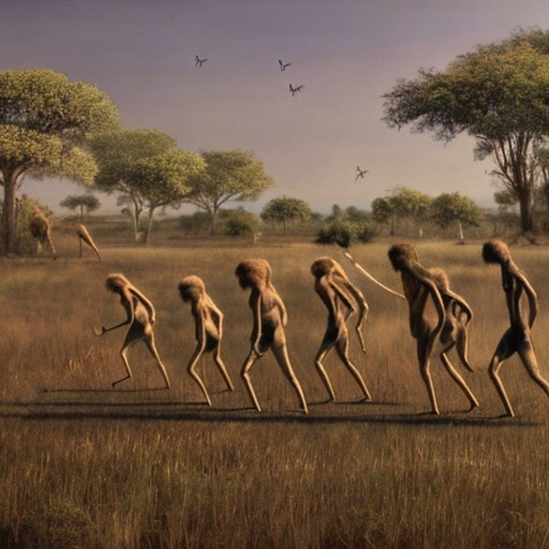

In the late Miocene era, roughly 10 million years ago, as the planet’s climate began to cool and dry out, animals all over were forced to adapt to the pressures of natural selection.

For this reason, the great apes—our early ancestors—who lived in the tropical rainforests were finding themselves increasingly forced into ever shrinking environmental niches.

Due to decreased rainfall, the shrinking rainforests and expanding grasslands led to the extinction of many primates unable to adapt to the shifting landscape and its impact on food availability.

One species to successfully survive such challenges were the anthropoid apes—our ancestors—who took to the newly exposed grasslands in search of sustenance.

Try This Delicacy, Won’t You?

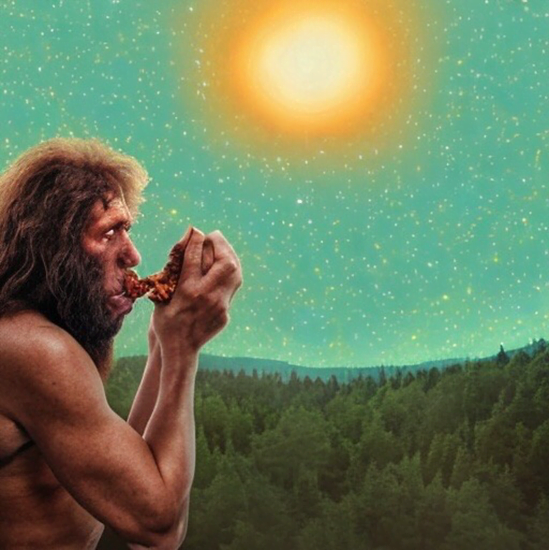

As they became bipedal and swung down from the trees to the grasslands, proto-hominids went from a strictly fruit-based diet to one that included insects, animal flesh and began to test whatever they found for possible inclusion.

Alongside our ancestors’ evolution, a parallel one was occurring: that of large, herbivore mammals, (meaning primitive cattle and wildebeests.)

These mammals congregated in herds on the grasslands, and if they could be successfully hunted, constituted a potential deposit of concentrated protein.

As an adaptive realisation, our ancestors soon found that hunting and consuming animal protein was far more nutritious than, for example, raiding an anthill, or gorging on large quantities of fruit.

And so it was that in time we would switch from an omnivorous to an increasingly carnivorous diet, adopting a nomadic pastoralist existence, following such herds across their migratory routes.

Curiously enough, it is an established fact that psilocybin mushrooms flourish particularly well in the dung of herbivore mammals such as the herds we began to chase.

The Magic of Mushrooms: Their Adaptive Benefits

Early hominids, McKenna points out, would soon discover that eating psilocybin mushrooms conferred at least three main adaptive benefits, in evolutionary terms.

- Visual Acuity:

Psilocybin, while inducing intense hallucinations in large doses, likely appeared in early hominids’ diets in small amounts, as McKenna suggests. Low doses, proven to enhance visual acuity in humans, may have introduced the benefits of “microdosing” to foraging primates 300,000 years before its recent popularization— a significant game-changer.

- Central Nervous System Arousal: In essence, small psilocybin doses could have made early hominids…well…hornier, for want of a better word—a known side effect of the compound. This heightened libido may have spurred demographic booms, conferring a competitive edge to those consuming psilocybin and passing this knowledge to their offspring.

- Pleasure + Curiosity: McKenna suggests that some early hominids, possibly enjoying mushrooms’ hallucinogenic effects, may have consumed more than strictly necessary. Higher psilocybin doses are known to stimulate Broca’s Area, the brain region responsible for language production.

In the Beginning Was the Word

Language, McKenna points out, is the great divide between us and other species, in the sense that where it exists in animals, it is generally restricted to practical information about their immediate surroundings.

As far as science knows, animal communication does not deal in the abstract or the imagination, which is what sets us apart from the animal kingdom.

In humans, he argues, consciousness—or “awareness of awareness” as he terms it— seems to have been our ultimate goal, since after acquiring consciousness and developing language, our physical evolution stopped altogether.

Through extensive language development, we appear to have bypassed the slow process of species modification, where environmental selective forces generate random adaptive DNA mutations—a process proven by science to take billions of years.

Top of Form

Therefore, because of psilocybin, our evolution swung from being predicated by genetic coding, and instead began to hinge on epigenetic coding—language, dance, art, ecstasy, mystical experiences and storytelling—in short: culture.

Speaking in Tongues

In sufficiently high doses, psilocybin produces a reaction termed “glossolalia”, also known as “speaking in tongues.”

It is a phenomenon in which an individual vocalizes a seemingly unintelligible string of syllables, words, or phrases, often as part of a spiritual or mystical experience before they have found previously known words to describe it.

The person engaging in glossolalia typically appears to be speaking in a language that is unknown to them or does not yet exist, and their speech often lacks any discernible grammatical structure or meaning.

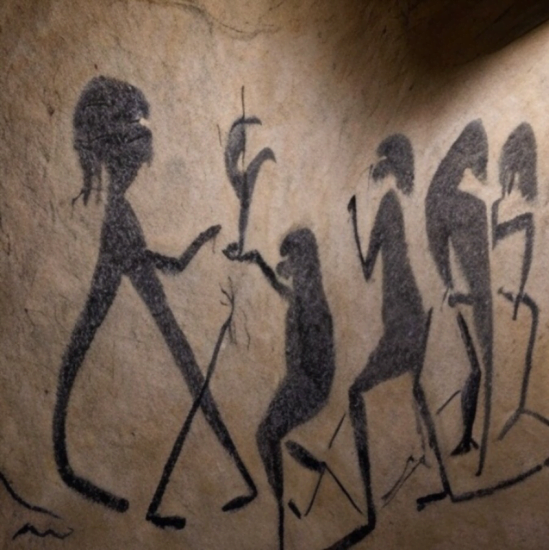

In anthropology, this vocalizing of language-like activity is considered a sign of “shamanism”: the ability to weave story, create myths, and find new words to communicate abstract thought.

Through this increased frequency of attempted and improvised speech, we began to convey new emotions and meaning, and exploring our newfound imagination, began telling stories.

With story, came myths; with myths, the seeds of culture were sown.

Culture, essentially, is just that—the crystallization of the organized structure of human imagination through the medium of language.

On a purely neurophysiological level, other scientists have speculated that the more we vocalized, the more cerebrospinal fluid we produced, which further refined our brains.

This, McKenna posits, is what may have led to the inexplicably rapid increase in early hominid brain size, an explanation which even the more mainstream theories have failed to fully account for.

Women, Language and Agriculture

Due to the physically demanding nature of hunting, female Homo Sapiens primarily took on the roles of gathering, nurturing and agriculture.

Consequently, those who possessed a more comprehensive knowledge of food sources and preparation techniques naturally held a significant advantage within their communities.

According to McKenna, the activity of gathering, knowing, and communicating the properties of different plants and foods conferred upon humans the game-changing advent of agriculture.

In spite of all their botanical knowledge, and to the detriment of human history, women would later bear the brunt of patriarchal society, from the rise of Christianity, which blamed them for the eating of the “forbidden fruit” and expulsion of mankind from proverbial paradise, right down to the persecutions of the Spanish Inquisition, general witch-hunting mentalities and present-day misogyny.

However, by selecting only those plants that mattered, our formerly nomadic communities began to cultivate, and therefore live a more sedentary lifestyle.

No Pain, No Grain: a Reappraisal of the Agricultural Revolution

Through no fault of womankind, the Agricultural Revolution, sadly, would prove a double-edged sword.

Often, the stories we are told are not always true, and in line with this, what we have been taught about the Agricultural Revolution has led to the misconception that humans had successfully domesticated and tamed nature.

In his brilliant reappraisal of human history, author Yuval Noah Harari, in his book “Sapiens: a Brief History of Humankind” suggests the opposite occurred.

We were, quite literally, domesticated by nature.

The shift to agriculture is widely thought to have begun around 9,500-8,500 BC in areas like southeastern Turkey, western Iran, and the Levant (also known as the Fertile Crescent).

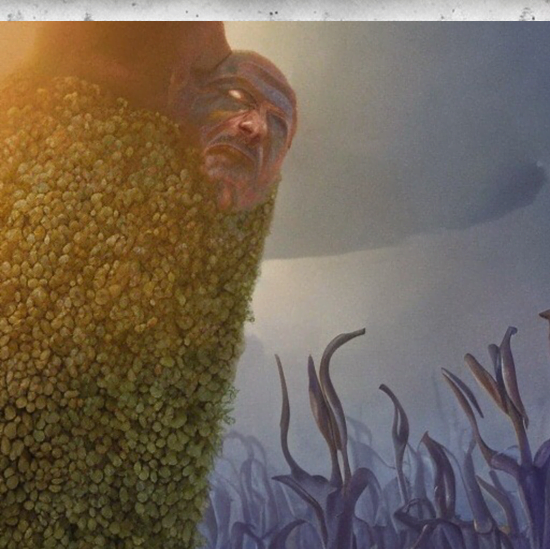

Harari notes that 90% of the calories sustaining humanity today come from grains domesticated between 9,500-3,500 BC, including maize, rice, wheat, barley, potatoes, and millet.

However, the overlooked reality is that life for the average farmer during this period was more laborious and challenging than for their foraging ancestors.

Harari argues that humanity was, in fact, “domesticated” by a few types of grains.

“Wheat did it by manipulating Homo Sapiens to its advantage. This ape had been living a fairly comfortable life hunting and gathering until about 10,000 years ago, but then began to invest more and more effort in cultivating wheat. Within a couple of millennia, humans in many parts of the world were doing little from dawn to dusk other than taking care of wheat plants.”

And so it was that farmers had no choice but to settle permanently next to their wheat fields.

If the success of a species is measured in the number of copies of its DNA; then, and only then, was the agricultural revolution a success: because it kept more people alive, indeed…but under far worse conditions than before.

The Beginning of Our Split from Nature

Although both authors wrote in different decades, Harari seems to agree with McKenna on this: that the Agricultural Revolution marked the beginning of the dualistic power-struggle between man and nature.

For McKenna, the use of hallucinogens began to dwindle with the passing of hunting and gathering societies.

For agriculturists, it was no longer tenable to indulge regularly and fully in such substances, for how could they till the field in a labor-intensive day?

And so, a new set of Gods emerged: those of corn and grain, with their own set of demands.

With the abundance of overproduction came wealth; with it, as corollaries, came trade, but also hoarding.

Trade and surplus wealth would in time lead to cities, which only served to further isolate their citizens from nature.

Cities would be governed by self-appointed male elites in charge of the surplus wealth generated by the toil of the people. The rest, we may say, is HIStory.

And this, with our host of latter-day maladies such as depression, trauma, addiction and a pandemic sense of selfishness stemming from lack of nature, nurture, community and roots, is where we find ourselves now.

Criticisms and Counterarguments

Lack of Evidence

As beautifully constructed and researched as McKenna’s “Stoned Ape” hypothesis is, it has faced criticism due to the lack of concrete evidence supporting the theory.

Critics argue that there is insufficient archaeological or genetic data to prove a direct connection between magic mushroom consumption and human evolution.

Mainstream Theories

Some researchers have been canonised for their theories on the development of human cognition, such as the social brain hypothesis, which suggests that the complexities of social interactions drove the evolution of human intelligence.

Yet, while they may hold some truth, they are far from the full story.

Others point to the role of tool-making, language, and other cultural factors in shaping the development of human cognitive abilities.

While not disparaging the validity of the above hypotheses, it is necessary to consider that, as with any “alternative” theory such as McKenna’s, the established order’s natural tendency is that of resistance.

In light of the criticism he received in the 1990s, after the publication of “Food of the Gods,” he adds that:

“Like sexuality, altered states of consciousness are taboo because they are consciously or unconsciously sensed to be entwined with the mysteries of our origin—with where we came from and how we got to be the way we are. Such experiences dissolve boundaries and threaten the order of the reigning patriarchy and the domination of society by the unreflecting expression of ego.”

“Nothing (But Flowers)”

Indeed, if we are to evolve, especially in the current and very damaging climate of the “culture wars” which pit Left against Right well beyond politics, affecting almost all areas of social discourse, then it is imperative we keep an open mind.

Not only this, it is important that we soften our egos to the possibility that there are no absolute truths in life, therefore allowing diversity of thought, magic and mystery their appropriate role in how we perceive the world and the universe around us.

“Most of society’s arguments are kept alive by a failure to acknowledge nuance. We tend to generate false dichotomies, and then try to argue one point using two entirely different sets of assumptions…like two tennis players trying to win a match by hitting beautifully executed shots from either end of separate tennis courts.”

Tim Minchin, Comedian and Musician